Tilted Arc - Vandalism from Above and Below

There are few issues in the field of fine arts as controversial as public art. After the positive reception in the 1960s, it became obvious in the 1970s, that the responses to public art were negative in many cases. In this context, the US American National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) changed its policy in 1974. The newly developed guidelines state, that art in public spaces should adapt the requirements of the location where it is intended to be installed. Site specificity was introduced to public policy.

The site specificity of contemporary art evolved from minimal art. Douglas Crimp refers to site specificity as the dialectical response to modernism with its system of museums, galleries and collectors. With their site specific works, artists make a stand against the aesthetics of commercial goods and thus, mobile art. Site specificity is to be understood as a reaction to the so-called “drop sculptures” by artists such as Auguste Rodin or Henry Moore, whose castings, as Rosalind Krauss puts it, are positioned in different places (art galleries, public spaces, private rooms) without context around the world. Site specific art is created for a specific place. That’s why site specific working artists assert the claim of authenticity and originality within the meaning of Walther Benjamin. While the concept of modern sculpture always strives for independence from the site, minimal art focuses on the surrounding space and the present recipient. According to Douglas Crimp, site specific art debates the idealism of modern art through the involvement of the recipient. While in modern art, the artist plays the role of the subject, this position is attributed to the recipient of site specific art. The aim is to receive the site not only in its physical reality but also as a cultural structure.

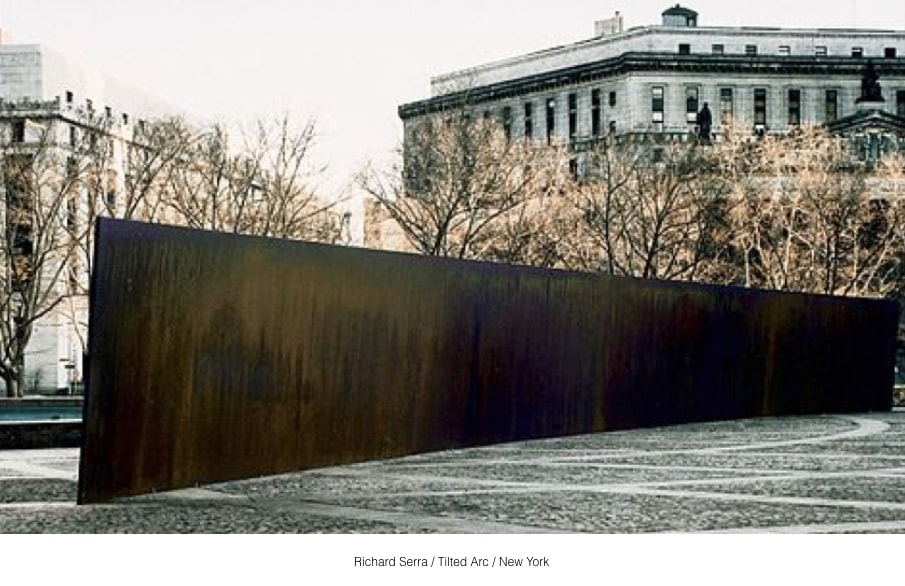

Rosalind Krauss compares site specific art with the concept of postmodernism and artists such as Richard Serra. While Carl Andre, among other artists, defines site specificity rather abstract and works with spatial categories, Richard Serra defines sites as unique. The sculpture Tilted Arc manifests the radicalization of site specificity by Serra. However, the reactions to the artwork also clarify, that site specificity provides no definite solution for public art. The US government commissioned by Serra a permanent sculpture for the Federal Plaza in Manhattan, NY. A 36.6 m long and 3.66 m high, slightly tilted steel sculpture named Tilted Arc was installed in 1981. The site specificity of the artwork is displayed through various aspects, such as the form, the scale, the material and the placement of the sculpture in relation to the Federal Plaza. The sculpture adopts the rounding of the fountain and the variation of semicircles of the pavement design for instance.

Despite the supposedly inclusive site specificity towards the plaza, office workers, who were confronted with the artwork on a daily basis, responded negatively. The Federal Plaza based judge Edward Re began a campaign against Titled Arc in the same year the sculpture was installed. In a letter from 1981 he claims that the wall, as he describes Tilted Arc, not only destroys the beauty, but also the utility of the plaza. In 1984, William Diamond, the recently appointed regional administrator of the GSA in New York, started to show interest in the case. He organized a public hearing in which it should be decided whether or not Tilted Arc should be dismantled. During the public hearing (6th-8th March 1985) 180 statements were heard. 122 people voted for the sculpture and 58 voices pleaded for the removal of Tilted Arc.

Among the advocates of Tilted Arc were mainly artists and curators, like Claes Oldenburg, Frank Stella, Louise Bourgeois, Leo Castelli, Frank Gehry, Keith Haring, Donald Judd, George Segal, Benjamin Buchloh, Douglas Crimp and Rosalind Krauss. Their main argument was the site specificity of the sculpture. As reported by Serra, there was a legal connection between the artwork and the Federal Plaza. According to the guidelines of the GSA, Tilted Arc was intended to be “an integral part of the total architectural design.” Because of it’s site specificity, Tilted Arc would lose its meaning and therefore would be destroyed, if put in another location. In a letter to Donald Thalacker, Serra describes his central thesis of iconoclasm.

Tilted Arc was commissioned and designed for one particular site: Federal Plaza. It is a site specific work and as such not to be relocated. To remove the work is to destroy the work.

The individuals who spoke out against the sculpture during the hearing were mainly concerned employees based at the Federal Plaza, who were confronted with the work on a daily basis. The spokesmen adapted the reasoning of Edward Re and William Diamond to a great extent. According to them, Tilted Arc was perceived as unattractive and aggressive because of its size. The effect of Tilted Arc on its location was considered destructive. Tilted Arc was described as a “mistake, nonsense, rubbish, the Berlin Wall and a scar on the plaza.” Moreover the opponents of Tilted Arc argued against the radicalism of the site specificity. Their attack was based on other artworks by Serra, which were supposedly intended for a specific location but then relocated without a massive protest by Serra, such as Clara Clara. Originally intended for the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the sculpture was positioned in the Jardin des Tuileries in 1983. Later, the sculpture was moved to La Défense and the dismantled in 1993. In 2008, Clara Clara returned temporally during the Monumenta to the Tuileries. Clara Clara is not the only site specific work by Serra which was relocated. Berlin Junction and Sight Point are other examples. Firstly installed in front of the Martin Gropius Bau in Berlin, Berlin Junction was repositioned next to the Berlin Philarmony. Sight Point was originally designed for the Weseleyan University in the USA, but installed in the garden of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1972. Interestingly, the design of the Museumsplein was changed in the last few years. Barely moved, Sight Point is not standing in the garden of the museum anymore, but in front of the main entrance of the museum.

Despite the majority of advocates for Tilted Arc, the panel of the public hearing recommended to dismantle the sculpture. Serra therefore proceeded against the GSA. The lawsuit based on the violation of Serra’s right to freedom of expression. As soon as a means of expression is exhibited in public, the rights of the First Amendment apply, which forbids the state to suppress statements based on the content. In 1987, the US District Court dismissed the complaint. They argued that Tilted Arc is fully owned by the state and is installed on governmental owned ground. Serra forfeited his freedom of expression regarding Tilted Arc when he sold the sculpture voluntarily to the GSA. The GSA, as owner of the artwork, can freely decide about the whereabouts of the sculpture. Tilted Arc was dismantled on 16 March and destroyed regarding the site specificity four years after the public hearing. Today the work is still stored in a warehouse in Brooklyn.

While William Diamond celebrated the dismantling as a day of joy, Eric Brooks described the decision as failure of the American legal system:

The loss of “Tilted Arc” forcefully illustrates the failure of U.S. laws to protect the visual artist’s moral rights of paternity and integrity. Removal of any site specific sculpture from its context, even if relocated intact, by definition violates the integrity of the work, resulting it its conceptual destruction.

Serra compares the demolition of Tilted Arc with book burnings, while Benjamin Buchloh designates the case as vandalism from “above” and illegal show trial in retrospect. The use of the term vandalism from above is reminiscent of Martin Warnkes distinction of iconoclasm from above and below. Iconoclasm describes originally the destruction of religious statues. By present meaning, the term stands for the resistance to images and art in general and in a metaphorical sense, the attack of institutions and beliefs. This dimension has its origin in the French Revolution. The idea of revolution is parallelized with the idea of iconoclasm. In connection with the French Revolution, however, not only the concept of iconoclasm, but also the term vandalism is used. Vandalism marks the destruction as barbaric. While iconoclasm implies an intention, vandalism represents an arbitrary action. According to Martin Warnke, iconoclasm from above is celebrated as a great event in the history of art, if it managed to surpass the aesthetic quality of the eliminated works. The iconoclasm from below is denounced as blind vandalism. According to Benjamin Buchlohs characterization, Tilted Arc has ben replaced by new symbols. The GSA supports projects that seem to be appropriate to the public taste. After the demolition of Tilted Arc, benches and plants were installed at the Federal Plaza.

Miwon Kwon compares the case of Tilted Arc with the so called culture wars:

The Tilted Arc incident made most clear that public art is not simply a matter of giving „public access to the best art of our times outside museum walls.“ In fact, much more was riding on the Tilted Arc case than the fate of a single art work. Unlike prior public art disputes, this controversy as one of the most high profile battlegrounds for the broadbased „culturewars“ of the late 1980s, put to the test the very life of public funding for the arts in the United States. In the tide of neoconservative Republicanism during the 1980s, with the attack on governmental funding for the arts (…) reaching a hysterical pitch by 1989, public art programs had to strategically rearticulate their goals and methods in order to avoid the prospect of annihilation or complete privatization.

The case of Tilted Arc was interpreted as a neoconservative campaign to privatize culture and to censor critical art. Serra and his advocates assumed that the fight against Tilted Arc had nothing to do with the public opinion but with the political aspirations of the Republican and GSA Administrator William Diamond. According to Benjamin Buchloh, the attacks against public funded art don’t only focus on Serras art but public art in general. In his text “Censorship in the United States” from 1989, Serra compares the Tilted Arc incident with the censorship of Robert Mapplethorpe photographs. The Corcoran Art Gallery cancelled a Mapplethorpe exhibition after the public criticism grew larger and larger. While a violation of public decency was used in the Mapplethorpe case, the opponents of Tilted Arc played with basic fears of the public. Vickie O’Dougherty, a GSA worker, presented safety concerns. Due to the size and the positioning of the sculpture, it was argued that the security personnel could not overview the Federal Plaza. According to her, drug dealers would use the space due to the complexity of the plaza. Concerns were, however, not only that Tilted Arc would disturb the surveillance, but also that terrorists could use the sculpture as a bulkhead. Tilted Arc was particularly well suited for potential terrorist attacks because it would direct the explosion forces not only upwards, but also at an angle to both buildings. Tilted Arc is not the only artwork where opponents played with such fears. The Baltimore Federal by artist George Sugarman was accused to serve as a hiding place for potential thieves or terrorists. Further examples of this vandalism from “above” are the removal of the facade installation Thirty Most Wanted Men by Andy Warhol of the New York World’s Fair (1964) and the removal of a mural by Robert Motherwell from the Federal Building in Boston. The Robert Motherwell artwork had implications for the Architecture Program. It was closed for six months because of the scandal. Tilted Arc also had implications for governmental programs. In response, 25 projects of the Architecture Program were stopped in order to formulate new guidelines, which reinforced the influence of the local authorities and architects in the selection of artists.

An analysis of the reactions towards Serra’s sculptures in public spaces and public art in general shows, that it would be too narrow to conventionalize the Tilted Arc case merely as a republican´s battle against the contemporary art world. The protests against art by Serra and public art in general isn’t limited to the USA. There are also cases in Europe, such as the already mentioned dismantling of Clara Clara. It is striking, that Clara Clara as well as Tilted Arc were covered with graffiti before the dismantling. Moreover there are numerous other examples from Serra’s oeuvre, that were defaced with graffiti and posters, such as Torque, Berlin Block for Charlie Chaplin, T.W.U., Sight Point and Terminal. Therefore the vandalism against Serra arises not only from above but also from below through citizens. Vandalism from “below” is no new phenomenon. Works of other artists become victims of vandalistic attacks frequently.

There are plenty of explanations for attacks on public art. The controversial so called “Broken Windows Theory” is one of the broadly known theories regarding vandalism. In 1969 the psychologist Philip Zumbardo suspected that signs of decay increased destructive behavior. Based on this theory, the criminologist George Kelling and political scientist James Wilson developed a theory about the gradual deterioration of districts, which they described under the title Broken Windows in 1982. The theory states, that harmless transgressions, such as graffiti or littering lead to far worse deeds, because they create the feeling that the situation is out of control and no one is held accountable. It is interesting, that New York government officials, such as Rudolph Giuliani, who was also involved in the Tilted Arc case, used the theory as a basis for actions against petty felonies. Tilted Arc was used by the opponents as the origin for the decay of the Federal Plaza. It was argued, that the sculpture not only attracted graffiti, but also waste, urinating people and as a result, rats.

The question rises, why especially public art is the victim of vandalism, while vandalistic attacks against art in art galleries rarely occur. Obviously the safety precautions in museums play a big role. But it must also be considered that art in public spaces has another context as art, which is located in the area of art education. Art in public spaces not only confronts a public, which is explicitly interested in art, but also an involuntary audience. The involuntary recipients often only have guesses for the interpretation. According to Dario Gamboni, the pedestrian who comes in touch with art unwillingly, develops a sense of double exclusion. The exclusion of cultural practices and an exclusion from public space in general. As a result, art in public spaces can trigger a symbolic violence, to which the involuntary recipient responds iconoclastic. Walther Grasskamp explains the vandalistic attacks with the form of sculptures. Sculptures in public spaces can’t be decoded by “normal” recipients because of the lack of figurative forms. The loss of narrative significance is manifested in the rejection of abstract art in public spaces by the art historically untrained recipient. As a result, he labels public art to be doomed as a failure. Besides the shape, the material of sculptures seems to play a role. Serra provokes not just because of the abstract form, but also because of his choice of material. Since 1969 he uses COR-TEN steel, a fast rusting material. His art sets against to be purely decoration. Thus, during the process against Tilted Arc, the opponents not only denied the aesthetic quality and value of Tilted Arc but also the claim to art. It was described as a forgotten building component, that rather belongs to a scrap yard or in the Hudson River, as on the Federal Plaza.

However, the material and the form of Serra’s sculptures alone are not the whole explanation for the negative reactions of the recipients. To find an explanation, it makes sense to look at the character of Serras site specificity. Since the construction of Tilted Arc is based on the location, the question rises, why Serra provokes on various levels. According to Douglas Crimp, Serra does not work for locations but against them. Elisabeth Fritz explains the rejection of the recipient by the aggressive appropriation and occupation of the Federal Plaza by Richard Serra. In addition to the formal features, Serra draws attention to the social and political characteristics of the site in his site specific art. In this regard, it makes sense to take a closer look at the features of the surrounding buildings of the Federal Plaza. One of the buildings is the Jacob Javits Federal Building, which is the second largest government building in the US after the Pentagon. It contains the Social Security Administration, the US Citizenship and the Immigration Office, as well as offices of the GSA. The international trade court is also located at the Federal Plaza. Thus Tilted Arc was installed in a place that is public in a very specific sense. According to Douglas Crimp, the sculpture is located in the very center of the state power structure. Tilted Arc acted as a visual barrier in front of the Javits Building. Thus, the sculpture blocked symbolically the view of immigrants towards the USA, represented through the US citizenship and immigration office. According to Douglas Crimp, Richard Serra redefines the plaza. Douglas Crimp argues, that site specificity is always a political specificity, which is revealed in Serras art. Tilted Arc not only blocks the paths of the pedestrians but also contrasts the architectural style of the square design. The curvature of the sculpture opposed the rounding of the fountain and the pavement design. The direction of the curvature breaks the design of the cobblestones. Opponents of the sculpture used the argument of site specificity and reversed it, by explaining, that the geometric pattern of the paving stones is a site specific work of art that is now interrupted by Tilted Arc. According to the opponents of Tilted Art, the sculpture clashes with the plaza. Recipients faced the work as something forced upon them, an arrogant gesture by the government, that wanted to impose on them a certain taste. For that reason, the vandalism can be explained also through the concept of aggressive appropriation of public space through the piece of art. Tilted Arc can be described as well as vandalism from “above”.

Consequently, the case of Tilted Arc can be described not only as a battle for an artwork in public space, but also as a fight for public space in general. Serras concept of site specificity fails in the case of Tilted Arc. It shows that Serras approach does not solve the problem of art in public spaces but also encourages a debate the role of art in public spaces, a debate on rights, duties and the interest of the artist, the sponsors and the general public. The demolition of an provocative artwork, that challenges the recipient reveals, that the role of the public is reduced to that of a consumer. Public art is at risk of being abused as a decorative design element of public spaces. Therefore the demolition of Tilted Arc proves the paradoxes between art and politics, as Douglas Crimp notes:

Although Tilted Arc was commissioned by a program devoted to placing art in public spaces, that program seems now to be utterly uninterested in building a public understanding of the art it has commissioned. (…) What makes me feel so manipulated is that I am forced to argue for art as against some other social function. I am asked to line up on the side of sculpture, against, say, those who are on the side of concerts, or perhaps picnic tables. (…) I believe that we have been polarized here in order that we not notice the real issue: the fact that our social experience is deliberately and drastically limited by our public officials.

This raises the question to what extent the artistic freedom can be combined with the need of the public towards user friendliness and public law in a state regulated framework. It’s out of the question, that the public has the right to user friendly designed public spaces. But does the artists has to bow to the decoration demands? Paul Goldbeger, an architecture critic for the NY Times, argues, that artworks should be preserved, even if there is no total consensus. Governments should not bend to the pressure of individuals, when it comes to art in public spaces. But he also argues, that things are different, when there is an unanimous protest. Serra however raises the legitimate question, if something would remain, if you let the public vote about the displayed artwork in the MoMa.

Literature

ADB (Hrsg.), Projekt *005; Reader, Biel, 2010

Adriani, Götz (Hrsg.)/ Peters, Hans Albert (Hrsg.)/ Weyergraf, Clara (Hrsg.), Richard Serra, Bochum, 1978

Aminoff, Judith/ Gintz, Claude, Michael Asher and the Transformation of “Situational Aesthetics”, in: October, Vol. 66, 1993, p. 113131

Armbrüster, Tobias, Hurz am Bau, in: Die Zeit, 12. Juni 1992, Nr. 25

Baigell, Matthew (Hrsg.)/ Heyd, Milly (Hrsg.), Complex Identities; Jewish Consciousness and Modern Art, New Brunswick, 2001

Baker, George, The Other Side of the Wall, in: October, Vol. 120, 2007, p. 106137

Beardsley, John, Earthworks and Beyond; Contemporary Art in the Landscape; Third Edition, New York, 1998

Borden, Iain (Hrsg.) / Kerr, Joe (Hrsg.) / Rednell, Jane (Hrsg.), The Unknown City; Contesting Architecture and Social Space, Cambridge, 2001

Brenson, Michael, Public Art at New Federal Building in Queens, in: The New York Times, 24. March 1989

Brooks, Eric. M, Tilted Justice; SiteSpecific Art and Moral Rights after U.S. Adherence to the Berne Convention, in: California Law Review, Vol. 77, Nr. 6, 1989, p. 14311482

Buchloh, Benjamin, Michael Asher and the Conclusion of Modernist Sculpture, in: Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, Vol. 10, 1983, p. 276295

Buhr, Elke, Bitte nicht schießen, in: Monopol, 1. January 2012

Campagnolo, Kathleen Merrill, Spiral Jetty through the Camera’s Eye, in: Archives of American Art Journal, Vol. 47, No. 1⁄2, 2008, p. 1623

CathcartKeays, Athlyn, Is urban graffiti a force for good or evil?, in: The Guardian, 7. January 2015

Chave, Anna, Minimalism and Biography, in: The Art Bulletin, Vol. 82, Nr. 1, 2000, p. 149163

Crimp, Douglas, Richard Serra; Sculpture Exceeded, in: October, Vol. 18, 1981, p. 6778

Crimp, Douglas, Über die Ruinen des Museums, Dresden, Basel, 1996

Crimp, Douglas, Das Neudefinieren der Ortsspezifik, in: Crimp, Douglas, Über die Ruinen des Museums, Amsterdam, 1993

Deutsche, Rosalyn, Evictions; Art and Spatial Politics, Cambridge, 1996

Dia Center for the Arts (Hrsg.), Richard Serra; Torqued Ellipses, New York, 1997

Erlanger, Steven, Serra’s Monumental Vision; Vertical Edition, in: The New York Times, 7. May 2008,

Ferguson, Russel (Hrsg.), McCall, Anthony (Hrsg.), WeyergrafSerra, Clara (Hrsg.), Richard Serra: Sculpture 19851998, Göttingen, 1998

Foster, Hal (Hrsg.)/ Hughes, Gordon (Hrsg.), Richard Serra, Cambridge, 2000

Foster, Hal (Hrsg.), Richard Serra, Massachusetts, 2000

Foucault, Michel, Andere Räume, in: Barck, Karlheinz (Hg.), Aisthesis. Wahrnehmungen heute oder Perspektiven einer anderen Ästhetik, Leipzig, 1992, p. 3446

Friedman, D. S., Public Things in the Modern City: Belated Notes on “Tilted Arc” and the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, in: Journal of Architectural Education, Vol. 49, No. 2, 1995

Fritz, Elisabeth, To remove the work is to destroy the work; Ortsbezogenheit als künstlerische Strategie der Authentifizierung, in: kunsttexte.de, 01/2009 Gamboni, Dario, Zerstörte Kunst; Bildersturm und Vandalismus im 20. Jahrhundert, Cologne, 1998

Greasskamp, Walter (Hrsg.), Unerwünschte Monumente; Moderne Kunst im Stadtraum, 2 Aufl., Munich, 1992

GSA (Hrsg.), GSA Art in Architecture; Selected Artworks 19972008, 2008

Henke, Lutz, Digitales Feigenblatt, in: Monopol, 19. March 2015

Hieber, Lutz, Zur Aktualität von Douglas Crimp; Postmoderne und Queer Theory, Wiesbaden, 2013

Hobbs, Robert, MerleauPonty’s Phenomenology and Installation Art, in: Gianni, Claudia (Hrsg.), Installations Mattress Factory 19901999, Pittsburgh, 2001, p. 1823

Horowitz, Gregg, Public Art/Public Space; The Spectacle of the Tilted Arc Controversy, in: The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 54, No. 1, 1996, p. 814

Inaba, Jeffrey, Carl Andre’s Same Old Stuff, in: Assemblage, Nr. 39, 1999, p. 3661

Irwin, Robert, Being and Circumstance; Notes Toward a Conditional Art, Lapsis Press, 1985

Kaye, Nick, SiteSpecific Art; Performance, Place and Documentation, London, 2000

Kelly, Michael, Public Art Controversy; The Serra and Lin Cases, in: The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 54, No. 1, 1996, p. 1522

Kimmelman, Michael, Why Is This Museum Shaped Like a Tub?, in: The New York Times, 23. December, 2012

King, Jennifer, Perpetually out of Place; Michael Asher and Jean Antoine Houdon at the Art Institute of Chicago, in: October, Vol. 120, 2007, p. 7186

Knight, Cher Krause, Public Art; Theory, practice and populism, Malden, 2008

Kofman, Eleonore (Hrsg.)/ Lebas, Elisabeth (Hrsg.), Henri Lefebvre; Writing on Cities, Maiden, 1996

Kunstsammlung NRW (Hrsg.), Richard Serra; Running Arcs (For John Cage), Düsseldorf, 1993

Kwon, Miwon, Approaching Architecture: The Cases of Richard Serra and Michael Asher, in:Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin, State of the Art: Contemporary Sculpture, 2009, p. 4455

Kwon, Miwon, One Place after Another: Notes on Site Specifity, in: October, Vol. 80 (Spring, 1997), pp. 85110

Kwon, Miwon, One Place After Another; SiteSpecific Art and Locational Identity, Massachuchusetts, 2002

Latour, Bruno (Hrsg.)/ Weibel, Peter (Hrsg.), Iconoclash; Beyond the Image Wars in Science, Religion and Art, Karlsruhe, 2002

Lewitzky, Uwe, Kunst für alle? Kunst im öffentlichen Raum zwischen Partizipation, Intervention und Neuer Urbanität, Bielefeld, 2005

Light, Andrew; Smith, Jonathan (Hrsg.), Philosophies of Place, Boston, 1998

Mailer, Norman, The Faith of Graffiti, in: Esquire, Mai 1974, p. 77158

Matzner, Florian (Hrsg.), Public Art; Kunst im öffentlichen Raum, OstfildernRuit, 2001

Melville, Stephen, Richard Serra; Taking the Measure of the Impossible, in: RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, Nr. 46, 2004, p. 185201

Melzer, Chris, Der Stahlarbeiter; Der Künstler Richard Serra wird am Sonntag 75, in: Tageblatt, Nr. 254, 2014, p. 38

MerleauPonty, Maurice, Phenomenology of Perception, London, 2002

Meyer, James, Minimalism; Art and Polemics in the Sixties, New Haven, 2001

Meyer, James, Der Funktionale Ort, in: Kunsthalle Zürich (Hrsg.), Platzwechsel, 1995, p. 2439

Mundy, Jennifer, Lost Art: Richard Serra, in: Tate Blog, 25. Oktober 2012

MoMA (Hrsg.), Richard Serra; Sculpture, in: MoMA, Nr.38, 1986, p. 5

Nieslony, Magdalena, Richard Serra in Germany: Perspectivity in Perspective, in: RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, No. 53/54, 2008, p. 4758

O’Doherty, Brian, Inside the White Cube; The Ideology of the Gallery Space, San Francisco, 1976

Oettl, Barbara, Schwere Kunst nach Maß; Betrachterfunktion bei ausgewählten Blei und Stahlskulpturen im Werk von Richard Serra, Münster, 2000

Passmore, John, Richard Serra`s Tilted Arc, in: NYPR Archives and Preservation, 2013

Phifer, Jean Parker, Public Art New York, New York, 2009

Pollack, Maika, 13 Most Wanted Men: Andy Warhol and the 1964 World’s Fair at the Queens Museum, in: Observer, 30. April 2014

Reichenbach, Jens, Serra Skulptur beschmiert, in: Neue Westfählische, 31. January 2012

Rorimer, Anne, The Sculpture of Carl Andre, in: Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago, Vol. 72, Nr. 6, 1978, p. 89

Schenker, Christoph (Hrsg,), Hiltbrunner, Michael (Hrsg.), Kunst und Öffentlichkeit; Kritische Praxis der Kunst im Stadtraum Zürich, Zürich, 2007

Schlösser, Christian, Popularisierung des Musealen, in: Neue Züricher Zeitung, 10. Oktober 2012

Schwerfel, Heinz Peter, Kunstskandale; Über spontane Ablehnung und nachträglicher Anerkennung, Cologne, 2000

Senie, Harriet, The Tilted Arc Controversy; Dangerous Precedent?, Minneapolis, 2002

Serra, Richard (Hrsg.), Richard Serra; Sculpture 19851998, Los Angeles, 1998

Shapiro, Michael Edward, TwentiethCentury American Sculpture, in: Bulletin (St. Louis Art Museum), New Series, Vol. 18, Nr. 2, 1986, p. 140

Siebe Swart, Museumplein; work in progress, Rotterdam, 1999

Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawings, in: Gregory Battock (Hrsg.), Documentation on Conceptual Art”, Arts Magazine, Bd. 44, Nr. 6, New York, 1970, p. 45

Speicher, Stephan, Mahnmal für die NS”Euthanasie”Morde; Ausrufezeichen aus blauem Glas, in: Süddeutsche Zeitung, 3. September 2014

Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam (Hrsg.), Stedelijk Architectuur, Rotterdam, 2012

Stemmrich, Gregor (Hrsg.), Minimal Art; Eine kritische Retrospektive, Dresden, 1995

Strauß, EvaMaria, Kunst für alle; Interventionen im öffentlichen Raum, Diplomarbeit, Vienna, 2010

Szeemann, Harald (Hrsg.), Richard Serra; Schriften Interviews 19701989, Bern, 1990

Sutton, Benjamin, Kenny Scharf Smoked a Bong Inside a Richard Serra Sculpture, in: Artnet News, 14. September 2014

Treib, Marc, Sculpture and Garden; A Historical Overview, in: Design Quarterly, Nr. 141, 1988, p. 4358

Updike, John, Richard Serra Sculpture; Forty Years, in: The New York Review of Books, 19. July 2007

Warnke, Martin (Hrsg.), Bildersturm; Die Zerstörung des Kunstwerks, Munich, 1973

WeyergrafSerra, (Hrsg.)/ Bushkirk, Martha (Hrsg.), The Destruction of Tilted Arc: Documents, Cambridge, 1991

Wiehager, Renate, Conceptual Tendencies 1960s to Today II; Body/ Space/ Volume, Berlin, 2013

Wightman Fox, Richard; Lears, Jackson (Hrsg.), The Power of Culture; Critical Essays in American History, Chicago, 1993

Williams, Patricia, It`s Time to End Broken Windows Policing, in: The Nation, 8. January 2014

Wolf, Hertha (Hrsg.), Rosalind E. Krauss; Die Originaltität der Avantgarde und andere Mythen der Moderne, Amsterdam, 2000

Yale University (Hrsg.), Sol LeWitt and Conceptual Art, in: Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin, 2010, p. 126129

Zekri, Sonja, Der neue Bildersturm der PolPotIslamisten, in: Süddeutsche Zeitung, 20. July 2014

The image depicting Tilted Arc can be found in GSA Art in Architecture: Selected Artworks 1997 to 2008.